Pregnant at 15

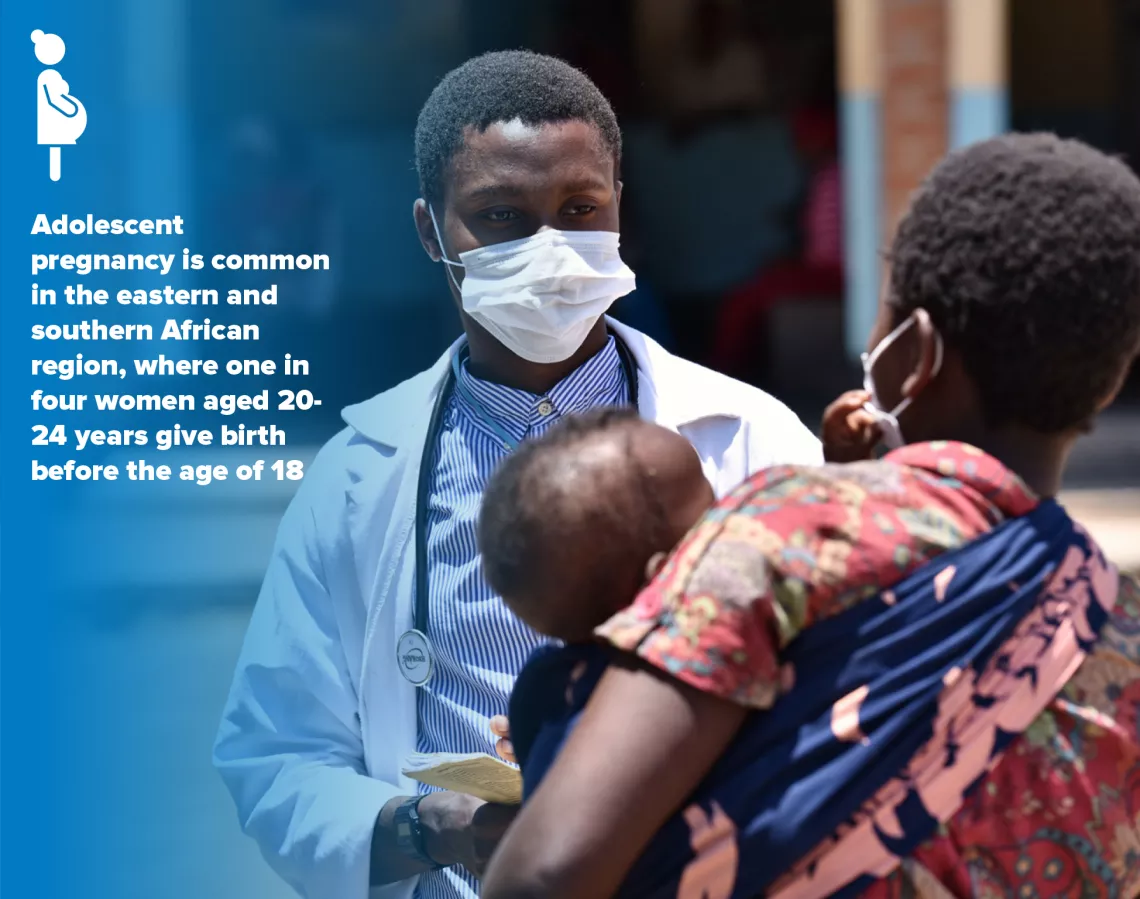

It’s early in the morning; 24-year-old Mary sits on a bench in the arid grounds of Malombe Health Centre in Malawi’s Mangochi district, bouncing her chubby nine-month-old baby girl. The only noises are her baby gurgling happily, birds singing and a cockerel crowing. She relates her story, at ease with the health centre’s senior medical assistant Henry Chimtengo by her side.

Mary shares how she dropped out of school at the age of 15 when she fell pregnant with her firstborn and lived for five years with the baby’s father, also a teen at the time. However, she says, his other relationships finally made her leave and take her son to live with her grandmother who is now in her 80s and is still Mary’s main support. Their living conditions are difficult; they have no electricity, no running water and they sleep on a mat on the floor.

Mary remembers how in 2019 she went to the health centre expecting to get medicine for her cough and in addition to her cough treatment she recalls receiving a range of other services, including family planning and HIV counselling and screening. Unexpectedly, she found out then that she was HIV positive. She received further counselling and a month’s supply of antiretroviral (ARV) drugs. “I was in denial, so I didn’t take the ARVs,” says Mary.

When Mary missed her next appointment, Chimtengo sent a community health worker to trace her and to offer further counselling. “I gradually learnt how to accept my situation,” says Mary. However, she was still too scared to tell her new boyfriend about her HIV status. “I thought he would leave me.” In fact, he left her when she became pregnant, apparently still unaware of her HIV status. Later, with further support from Chimtengo and his team, Mary mustered up the courage to tell him her HIV status and to persuade him to also test for HIV. Mary’s boyfriend tested negative for HIV and he also received counselling at the health centre. Their baby has also so far tested HIV negative (Mary is on the programme to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV). “I was so happy when my baby’s test came back negative,” says Mary. She now needs to wait until her daughter is 3 years old for the final HIV test, which is carried out once she stops breastfeeding. “I make sure I always take my ARVs, for not only my sake but for my baby’s sake,” says Mary. Her first child also tested HIV negative.

2gether 4 SRHR programme addresses adolescent pregnancies and well-being

Mary’s experience of adolescent pregnancy is common in the eastern and southern African region, where one in four women aged 20-24 years give birth before the age of 18, one of the world’s highest pregnancy rates. Moreover, 27 per cent of new HIV infections are among adolescent girls and young women aged 15-24 years. In total in the region, about 1.9 million children and adolescents are living with HIV.

To assist governments and communities in the region to address these issues, the joint regional 2gether 4 SRHR programme in eastern and southern Africa, in partnership with the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA), was launched in 2018.

The programme brought together the expertise of four UN agencies – the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and the World Health Organization (WHO) – to work with governments and partners, as well as regional economic organizations like the Southern African Development Community (SADC) to improve sexual and reproductive health. This includes scaling up client-centred quality assured integrated and sustainable sexual and reproductive health (SRH), HIV and sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) services, and empowering young people to exercise their SRH rights (SRHR).

Most health workers in rural areas aren’t specialists, so all health workers – whether a clinical health worker or a community health worker – received additional training to build up their capacity to provide sexual and reproductive health services. Creating demand for the services is also key. In Malawi, for example, local health centre advisory committees are also trained, which include relevant line ministry structures at community level to inform the people about the services and help link people who are hard to reach to these services.

Chimtengo adds that they still face challenges, including drug stock-outs, staff transfers and lack of public transport. There is no ambulance at the health centre, which has a catchment of 25,000 people. COVID-19 has also taken its toll. “We have had about a 50 per cent drop in people seeking health services,” says Chimtengo. “People think we will give them COVID-19.” Instead, people have been using outreach services, such as those provided by peer educators and community health workers. These outreach services have been strengthened as part of the programme.

As for Mary, she makes sure she comes to the health centre every three months to have her health and that of her children checked. If a family member is using her bike, she says, she makes the journey on foot – a two-hour trek. Her priority now is her family’s health and well-being.

(NB Mary is not her real name to protect her privacy)